Until now we have deliberately avoided the issue of calibrating your data. This means that your reduced data, up until this stage, are in units of volts. Since the calibration varies from night to night and even within a single night, one should generally calibrate individual maps before coadding to achieve the best result. So how does one convert instrumental units into a physical measure of luminosity or surface brightness? The solution as in most astronomy is to look at a source of known brightness in exactly the same way, i.e. using the same mode of observing for your target as well as for your calibrator(s).

In the optical and infra-red the standard sources are almost always point sources, standard stars, and the point spread function is well defined. In the submillimetre things are more complicated. Our primary calibrators, Mars and Uranus, are not point sources, and the point spread function is very extended and strongly wavelength dependent. The JCMT beam at 450 μm is actually much worse than the ill-fabled Hubble before the mirror was corrected.

The way we calibrate may differ depending on whether we observe point sources or extended sources. For point sources we can ignore the error beam and do simple aperture photometry, for extended sources we normally have to calibrate in Jy/beam and characterize our beam profile. In the following we first go through how to characterize the beam profile, then the case of calibrating in Jy/aperture and finally we proceed to the more general case of calibrating in Jy/beam, which is valid for all cases.

The calibration differs for jiggle maps and scan maps and it is also, although more weakly, dependent on chop throw. The relatively large difference in calibration for scan maps is due to the different chop wave form used for scan maps. The difference between a jiggle map with a 120” chop throw compared to one with a 60” chop throw is mostly dictated by duty cycle and to a lesser extent by changes in the beam. The beam is slightly broader with a 120” chop throw, but the duty cycle (time spent on source) is also slightly lower, both of these factors decrease the efficiency for large chops.

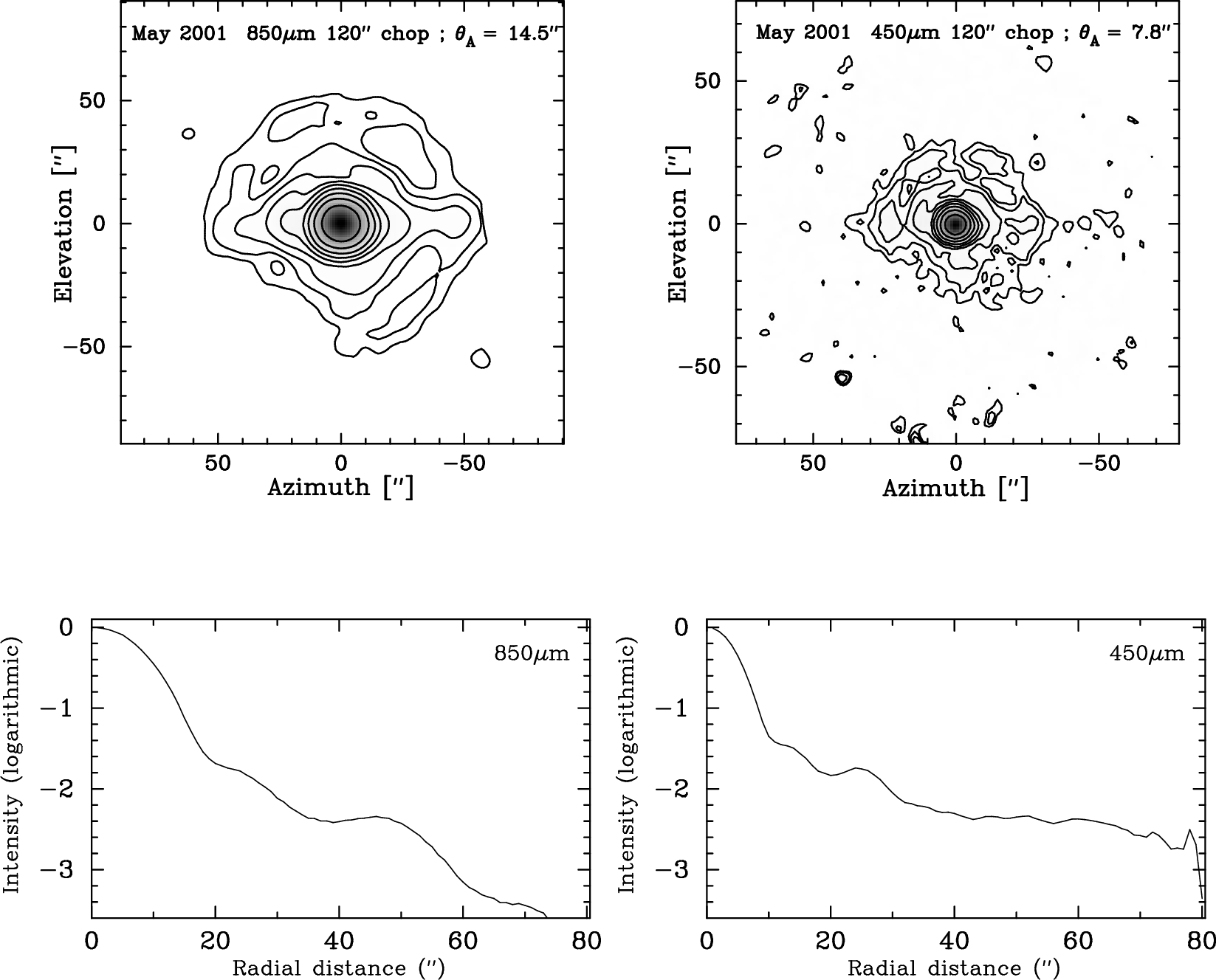

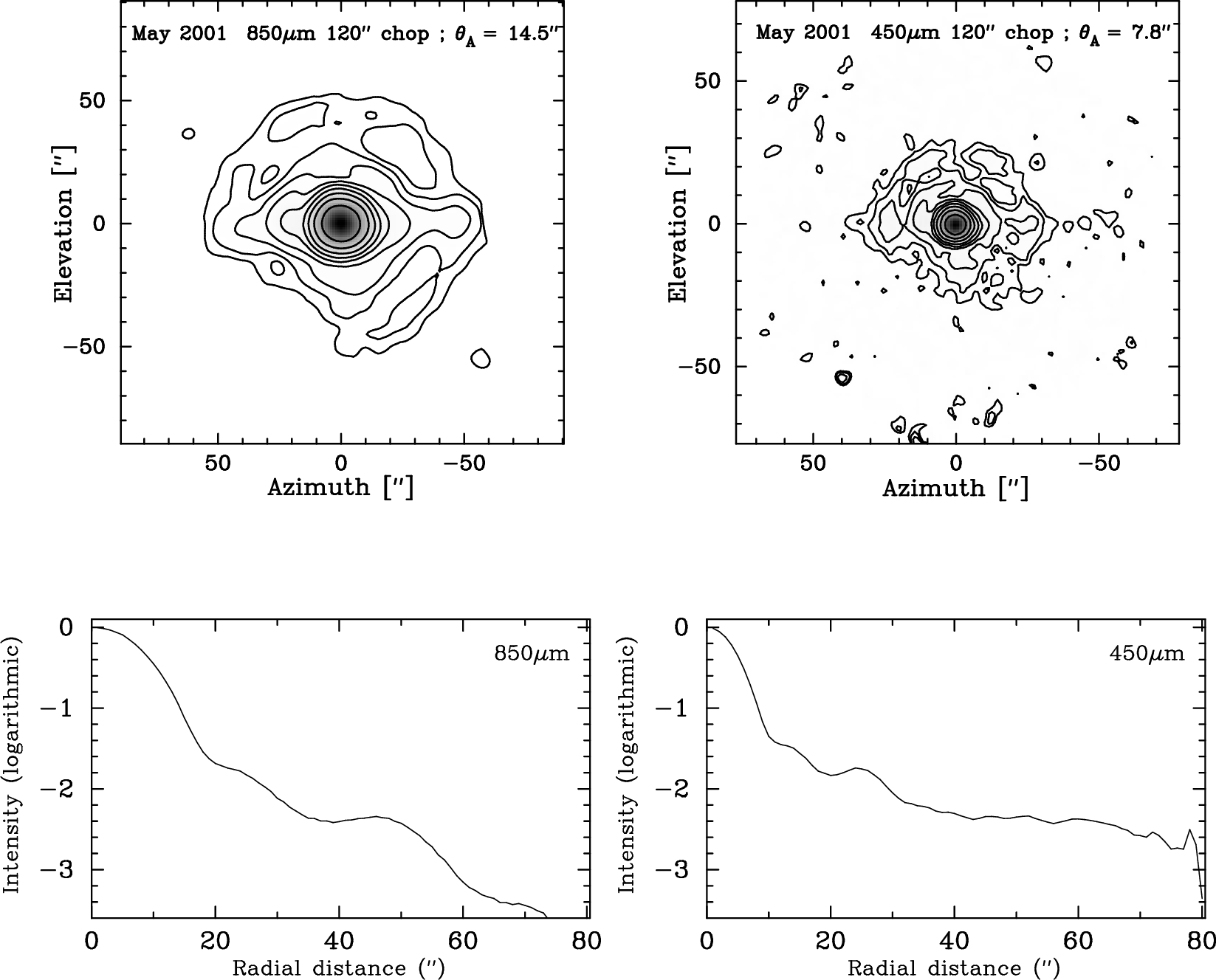

In the following example we are going to look at beam maps of Uranus taken in stable night time conditions during three nights in late May, 2001. These maps have been extinction corrected, we have blanked out bad bolometers and corrected each map for pointing drifts. There are slight calibration differences from night to night, but for this purpose the difference is negligible. The final coadded beam maps were rebinned in az and are shown in Fig. 11.

A quick way to diagnose that the beam profile looks reasonable is to use Kappa’s psf. The task psf fits a radial

profile, A×exp(−0.5×(r/σ)γ),

where r is calculated from the true radial distance of the source allowing for ellipticity,

σ is the profile

width, and γ

is the radial fall-off parameter. psf can also fit a standard Gussian profile. However, the JCMT beam is

better described by a two or three component Gaussian (main lobe plus inner and outer error lobes)

and psf therefore overestimates the Half Power Beam Width (HPBW). If we specify norm=nopsf will

also return the fitted peak value of the source.

This produces the plot shown in Fig. 12. The value of FWHM is 14.72” across the minor axis. The geometrical

mean is simply √mean axis ratio

times 14.72, i.e. the measured FWHM (including the broadening from Uranus) is therefore predicted

to be 15.4” if we use psf. However, if we fit a double Gaussian to the same data set we obtain 15.56”

×

14.30” with a position angle of 85 for the main beam, and 55.8”

× 49.6” for

the inner error lobe. To find the true (HPBW) we need to remove the broadening caused by Uranus being

an extended source. Using the program Fluxes (just type fluxes at the command line and answer the

prompts) we find out that Uranus had a diameter (W) of 3.54” that day. We convert the FWHM measured,

θm, to the true HPBW

of the telescope, θA,

using the equation

| θA=√θm2−ln22×W2 | (4) |

where W the diameter of the planet. In this case we get 14.5” for the HPBW and ∼ 53” for the near (inner) error beam. If we do the same for 450 μm we obtain 7.8” for the HPBW and 34” for the near error beam. These agree with nominal values for the telescope.

If your maps show simple source morphology and you are only interested in integrated flux densities, the simplest approach is to calibrate your map Jy/aperture for the aperture size you want to use. The listing of Fluxes also gives us the total flux, Stot for Uranus at 850μm is 67.9 Jy. Let us first see how we can use this value to calibrate our image in terms of Jy/arcsecond2. In order to do this we need to derive a value for the Flux Conversion Factor (FCF) which is in units of Jy/arcsecond2/V. To do this we first need to work out the sum of the pixel values (Vsum) in an aperture of radius r. We then find the FCF is given by

| FCF(Jy/arcsecond2/V)=67.9/Vsuma | (5) |

were a is the pixel area in square arcseconds. The easiest way to get the integrated signal in an aperture is to use Kappa’s aperadd. For our 850 μm map of Uranus we derive Vsum for a set of different circular apertures and compute the FCFs.

| Radius (arcseconds) | 20 | 30 | 40 | 60 | 120 |

| Vsum | 45.75 | 60.76 | 64.89 | 70.07 | 77.08 |

| FCF (Jy/arcsecond2/V) | 1.48 | 1.12 | 1.05 | 0.97 | 0.88 |

We can see from this table that the FCF is dependent on the aperture size that is used 1 This is because there is significant signal in the sidelobes and extended error beam of the telescope. Clearly then the value of FCF can be somewhat ambiguous. What you have to remember is that if you are doing photometry of an extended object, you should use a value for the FCF derived for the same aperture.

If you need to use small apertures, i.e. the size of your HPBW, you will need to use a point source or point like source as a calibrator. Flux densities for our secondary calibrators for a 40” aperture are given by Jenness et al. [14]. However, several of our secondary calibrators are not point sources. If you end up with, for example, IRC+10216 and IRAS 16293−2422 or Mars near perhelion as your only calibrators during your run, you are in trouble. You may be able to use a large aperture to recover all the flux and use the ratios between different apertures derived for a point source. But, you may as well bite the bullet and calibrate in Jy/beam.

If your images show a lot of structure, you will need to calibrate your maps in Jy/beam. This is true for most observations of dark and molecular clouds, young supernovae, protostars or young stars and even for nearby galaxies. However, if you are only dealing with faint point sources and low S/N maps, you probably need to integrate over the map. If this is the case, it does not matter whether you calibrate in Jy/beam or Jy/aperture, both methods will give the same result. Since Starlink packages do not deal with Jy/beam, it may appear more complicated to integrate over an image calibrated in Jy/beam, but the only difference is that one needs to normalize the integral over the source with the beam integral, ∫F(Ω)νdΩ, where F(Ω) is the normalized power pattern of the telescope. For a Gaussian beam the beam integral is simply 1.134×θ2A. Radio astronomical reduction packages of course do this normalization automatically. Since the JCMT beam is not a simple Gaussian beam, we need to account for the error beam, which is equivalent to having an FCF which varies with aperture, when we calibrate in Jy/aperture. We discuss how this is done towards the end of this section.

To calibrate in Jy/beam we have to know the beam size. Ideally we would derive both the flux density conversion factor and the beam size, θA, from planet observations. If there are no planets available, we can use one of the secondary calibrators. To determine the beam size at 850 μm it is usually sufficient to make a weighted average from our pointing observations during the run, if we don’t have a planet observation or a point like secondary calibrator, but for 450 μm we need a planet or a secondary calibrator. All JCMT secondary calibrators are directly calibrated in Jy/beam. In this case the FCF is simply the quoted flux divided by the peak signal of the source.

For a planet we have to account for the loss of signal due to the coupling to the beam, because all planets used for calibration are extended relative to the JCMT beam. For our Uranus data the flux density Sbeam is therefore the total flux density, Stot divided by the coupling of the planet to the beam, given by:

| K=x21−e−x2 | (6) |

where x is

| x=W1.2×θA. | (7) |

The FCF, in Jy/beam/V is therefore

| FCF(Jy/beam/V)=Sbeam/Vpeak | (8) |

For 850 μm we find K = 1.021 for θA = 14.5”, which gives Sbeam = 66.5 Jy/beam. The peak signal that we found for our high S/N Uranus map, Vpeak = 0.2477 V, or an FCF = 268.5 Jy/beam/V. This FCF applies to a jiggle maps with a 120” chop throw. If we do the same for our jiggle maps of Uranus with a 60” chop throw, we derive FCF = 245.2 Jy/beam/V, i.e. a map with a 60” chop throw is ∼ 10% more efficient than one with a 120” chop throw. Even though Jenness et al. ([14]) found no difference in FCF as a function of chop throw when calibrating in Jy/aperture we find that the difference is now smaller than compared to when calibrating in Jy/beam but still noticeable. For a 40” aperture the difference is 6%.

If we use a secondary calibrator to calibrate our maps, it is even simpler. We just take the quoted flux value, Sbeam, from the secondary calibrator page and divide it with the peak flux in our map of the same calibrator. If the map of the calibrator has poor S/N, we may want to fit a gaussian to the source to get a more accurate measure of the peak signal.

Analyzing maps calibrated in Jy/beam is easy; especially if we want to deduce flux densities for point sources or compact sources even when the source is embedded in a cloud with strong extended emission. For a point source the peak flux of the source is the same as the total flux corrected for any background emission. For an extended source we need to measure the FWHM and correct it for the measured HPBW of the telescope. We normally do this by fitting a double Gaussian, one for the source and one for the background. At 850 μm the fitted peak signal minus background, Speak, is now the peak flux density measured in Jy/beam. From the fitted Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) we can derive the true FWHM, θs, by deconvolving with the measured HPBW, θA. This is trivial, because now we can assume a Gaussian source and a Gaussian beam. After we know the source size, θs we multiply the peak flux with the correction factor we derive from the size, i.e. for a spherically symmetric source with the source size, θs, the total flux, Stot is simply

| Stot=Speak×(1+(θs/θA)2) | (9) |

.

For 450 μm the error beam amplitude is no longer negligible, but when we fit a double Gaussian, the error beam will blend in with the extended cloud emission, i.e. it adds into the background level, or we may fit the source with a single Gaussian plus a second order surface, or whatever best approximates the background in a limited area around the source. From our analysis of the 450 μm beam maps of Uranus, we find that the combined error beam amplitude is of the order of 5% of the peak amplitude, and we should therefore multiply the peak signal by 1.05 before applying a source size correction (see e.g. Weintraub et al. [17]).

To find integrated intensities over large areas is more complicated, because now we need to correct for the error beam pickup, which now depends on the area we integrate over. This is equivalent to the varying the FCF as a function of aperture that one has to account for if the map is calibrated in Jy/pixel, but with the map calibrated in Jy/beam it is much easier to separate compact sources and extended emission. To determine the excess emission from the error beam, we again have to go back to our beam map. If we calibrate our 850 μm map in Jy/beam and then integrate over 120” circular aperture, we find that the flux we derive is 86.8 Jy, while we know that the total flux of Uranus is only 67.9 Jy. We therefore have to scale our derived total flux density by the ratio of true flux density over measured flux density (for our calibrated planet map), which in this case is 0.78. At 450 μm the situation is much worse. Even though the amplitude of the error lobe is still low, the area is large, and if we integrate over our calibrated 450 μm beam map we now derive 415.6 Jy, if we integrate over the same 120" circular aperture, while the total flux density from Fluxes is only 179.3 Jy. In this case our scaling factor is 0.43, i.e. we pick up more emission in the extended error beam than we do in the main beam.

For careful work, you may therefore want to deconvolve your SCUBA maps. This becomes especially important if you want to ratio the 450 and the 850 μm maps, because if you want to smooth the 450 μm map to the same resolution as the 850 μm map, you first have to remove the error beam. For example of how this can be done, see e.g. Hogherheijde and Sandell [13] or Sandell and Weintraub [16].

1During this time period SCUBA had reduced sensitivity due to a problem in the optics, affecting primarily the 850 μm array. Normally you would expect to find a FCF for a 40” aperture of 0.84, see Jenness et al. [14]